Rohulla Nikpai / Kabul

War games

Briefing

Winner of Afghanistan’s only Olympic medal, taekwondo athlete Rohullah Nikpai is a sporting icon. Yet, in a country where violence occurs everyday, winning the respect of his fellow countrymen means almost as much.

Rohullah Nikpai speaks the same way he fights: firmly and carefully. So when Afghanistan’s taekwondo champion is asked about his goals for the London Olympics, he pauses, fixes his gaze at monocle and replies without emotion: “I have always hoped to find a way to reach the Olympics and then get a medal.”

It’s this unflinching focus that won him just that in 2008. During the Beijing Olympics Nikpai secured his nation’s first Olympic medal after beating Spanish world champion Juan Antonio Ramos in the 58kg category. In a country that’s endured more than 30 years of war and where the value of a man is based on his fighting skills, his victory has made him a cult figure and a symbol of national pride. Thousands of Afghans poured into Kabul’s Ghazi Stadium – a place once used by the Taliban to stage public executions and stoning – to celebrate Nikpai’s arrival home.

Nikpai’s physical achievements are considerable. Today at the National Olympic Committee training centre in Kabul it takes him 40 minutes of sidestepping, kicking and hopping across the blue and red mats at his coach’s command to even break a sweat. “Hit harder, open your leg wider to let your kick fly freely,” says coach Mohammad Bashir Taraki. “For the London Olympics we have put up all our efforts to win a medal. We have confidence in Nikpai. We hope he gets a gold medal this time.” But his most impressive feat has been his ascent from a background of poverty and social unrest. As a Hazara, Afghanistan’s ethnic minority of Shiite Muslims who have endured a history of discrimination (especially by the Pashtun Taliban who ruled the country from 1996-2001), his family were forced to flee to neighbouring Iran in the 1980s. Nikpai was taught taekwondo by his brother in the Iranian refugee camp he was raised in.

When Nikpai and his family returned to Kabul in 2004, the Taliban had gone and the shaky building blocks of a new society were being levered into place. Although peace was (and perhaps is) still far off, the stadium was no longer being used for acts of atrocity and sport had once again returned. The Kabul Taekwondo Federation welcomed this refugee newcomer and he quickly progressed up the national ranks. “After I returned to Afghanistan I started taekwondo as a professional and joined the national team,” he tells monocle. “When I found out that taekwondo was an Olympic game, I fell in love with it even more.”

His bronze medal in Beijing was a turning point in Afghanistan’s sporting history. Under the Taliban, athletes had to grow beards, stop a match if it was approaching prayer time and wear impractical long trousers. So the progress Afghanistan is witnessing is startling.

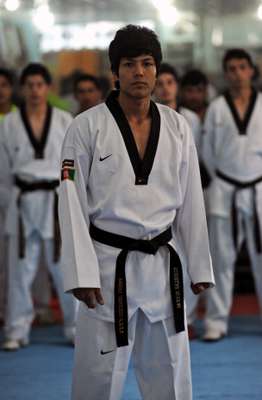

Nikpai’s successive achievements have inspired a record number of Afghans to take up taekwondo. Today the 15 young men in white kit who surround him, all with afg and Afghanistan’s flag printed on their clothing, are just some of the people who have signed up for the sport. “Nipa-e qaraman, qaraman beman” says a poster with Nikpai’s picture on it at the entrance of the gym, meaning “Nikpai the hero, always remain a hero.” He knows things have changed. “I’m an icon now and I want to be an example to others,” he says with a triumphant smile.

Sporting role models in Afghanistan serve as a small window of optimism in a country still devastated by war. Afghanistan has qualified for the t20 Cricket World Cup in Sri Lanka and its football team recently lost at the final of the South Asian Football Federation Cup.

But life as an Olympian in Kabul is hard. Although in the immediate aftermath of Beijing, Nikpai was given a house, a car and some money, he says he and his teammates still do not have the facilities most athletes in other countries have. “If you compare us with other countries, there is a big difference. We don’t even have a standard place to work out,” he says. “An Olympian’s mind should be in peace all the time. He has to be paid well, he has to be supported, he has to have a good doctor to take care of him if he gets injured. Unfortunately we don’t have a doctor, we don’t have a psychologist. We don’t even have a food expert to tell us what to eat. But it is only our love for our people and country that will eventually lead us to success.”

Unlike most Olympians he also works full time in a local private electronics company in Kabul to support his six-member family. He tells monocle how Afghanistan’s National Olympic Committee only pays a monthly stipend of afn700 (around €11) and this often fails to materialise. “I don’t make any money through my profession. I have to both work to make a living and workout hard to prepare for the Olympics,” he says. “If little attention is paid to sports, if we continue to get very little support from the government, we won’t get good results in the future. I hope the government pays more attention.”

At Nikpai’s home, an apartment in the north of Kabul, a present from President Hamid Karzai, a cabinet is filled with shiny medals and colourful ribbons he’s amassed since he was 19. For now, nothing can distract Nikpai from going to London and trying to win more medals – not even his fiancée. “I won’t marry until I finish the Olympics in London successfully,” a smiling Nikpai says. Silverware has become an intensely personal part of the young champion’s life. But there’s no doubt that his coach, and a war-torn nation, will be willing him on to win gold.