Social housing / Global

Estate of the art

A progressive 1960s concrete estate in the middle of precious woodland might send alarm bells ringing in many design circles. But Siedlung Halen just outside Bern is a quiet, friendly triumph where nurture sits alongside nature.

You don’t have to be a wizard statistician to know that demand for housing continuously outpaces supply. Be it greed or necessity, urbanisation or population growth, new homes are needed quickly, constantly. It’s an ongoing architectural conundrum of how to effectively build large-scale housing, where density, cost and quality of life for inhabitants are equally balanced. Not many get it right. It’s a less sexy task for architects than building a new opera house in China. But, by virtue of its difficulty and the fact that homes are needed, housing estates are still fertile ground for architects to flex their creative muscles.

The more enlightened have visited Siedlung Halen – the Halen Estate – five kilometres north of Bern, hidden in the depths of a fairytale forest, on a steep slope that runs down to the river Aare. Completed in 1961 by the young Bern-based practice Atelier 5, Halen is hardly a household name, even in the wider architecture community. And yet, more than 50 years on, it’s one of the most successful housing estates in existence.

It might never have happened. Atelier 5 initially sought to buy the patch of forest to build five single-family homes, one for each founding partner. But conditions (and cost) of the land sale meant they needed to fit far more than five houses onto their plot. Instead, they fitted 79. From above, less kind people have described the terraced rectilinear formation, made from brick and concrete, as a prison or chicken coop. Every house is three storeys, long and fairly narrow (3.86 or 4.81 metres wide), between 120-170 sq m in floor space and follows a basic six-room layout. You enter via a small courtyard garden into the middle storey, which contains a kitchen and living space and a terrace, big enough to fit a dining table and chairs. Upstairs are bedrooms, a bathroom and a small balcony. Downstairs could either be a home office or another bedroom, opening onto a long garden. A defining characteristic of the design is that no internal wall is structural, bar the ones connecting each house to its neighbour, so owners could make or break their interior layout however they liked.

Due to the fact the estate is built on a slope and the dividing walls between gardens are high, you feel miraculously private in any of the outdoor spaces. As one resident puts it: “You can sunbathe on the top floor balcony as god intended without anyone seeing.” It’s a privacy that’s difficult to imagine when you look at aerial photographs of Halen but it really does work. An air cavity separates each house from its neighbour for noise insulation (apparently only a piano can cross it) and once doors are closed you have no clue that you’re living in such close quarters next to so many people. Halen comes with a social code of sorts too. If the outside door that connects the small private courtyard of each house to the “street” is open, anyone can pop in.

The idea wasn’t that people would move here to escape others though, more that privacy was there if you wanted. And lack of privacy was what so many people feared when viewing the estate for the first time in the 1960s. Beyond its appearances one of Halen’s more groundbreaking concepts was the idea of shared ownership of communal spaces. These included a swimming pool, playground, shop, community hall, petrol station and garage. All bar the shop, which is currently closed, still work perfectly today. The resident maintenance man, Marcel von Mentlen, lives in house number 1 and is also the gardener who tends to the extraordinary jungle-like greenery throughout the estate.

After some difficulty Atelier 5 secured funding for Halen on the condition they would take responsibility for selling the houses, which was no easy task. By 1963, two years after the estate was completed, every house had finally been sold. Then they sold for around chf110,000 (€88,250) – today they’re no cheaper than an equivalent house in Bern. Yet the estate has been full for 50 years and residents tell stories of waiting for months and years for a house to come up so they could move here. The surprising thing is that it was not intended as a model for housing developments but rather an exercise in high-density, low-rise building and living that came about almost by accident.

Though it’s clearly influenced several housing developments from Mexico to Japan and everywhere in between, rarely if ever has a similar level of quality of life for inhabitants been achieved. “Nobody has had the courage to replicate the strictness of Halen’s design,” explains resident and architect Bernhard Egger. “Details are changed, garden walls are lowered, rooms are widened – but then the effect is diluted and the privacy or sense of community is weakened.”

Everyone talks of summer evenings spent in the open courtyard chatting over barbecues with beer. The swimming pool is a focal point too with more serious swimmers taking advantage of early mornings before work and families spreading out on the decking during the day. There are no cars in Halen – everything is reached on foot via well-lit open stairs or covered walkways, which take their cue from the loggias in the old city of Bern. The whole set-up is as perfect for children as it is for older folk, too.

If it sounds nauseatingly idyllic it might well be. Were Halen in any country outside Switzerland it would almost certainly be a hippy commune. But it works here; the people who live in Halen today are perhaps not best described as typical Swiss, though they’re definitely not hippies either. They are largely creatives – architects, designers, academics – the majority work in Bern (a 15-minute cycle away) and have fallen in love with Halen and the particular quality of life it affords. It may best be described as an upmarket suburb, surrounded by forest rather than city. It has the benefits of convenience and community found in an urban dwelling but with uninterrupted views over forests to the Alps, endless gardens and an unspoken mutual trust to the point that no door is ever locked.

Oliver and Veronika Slappnig

House 14

Graphic designer Slappnig and his wife moved to Halen in 1993, just after their first daughter was born. Three daughters and three moves within Halen later and they’ve settled. The Le Corbusier furniture they live with is hardly a style statement, more a perfect fit here, in homage to the man whose work and principles influenced Atelier 5.

Oliver, who works in a studio a few doors down and manages the bed and breakfast next door too, describes how he fell in love with it: “I grew up near Bern and used to come for parties here aged 18. It always looked so strange especially after dark.” The Slappnigs estimate that around 40 per cent of the houses at Halen are connected to their original owners. “Children grow up here and then move away,” explains Veronika. “Often they return when they have their own children – I can imagine one of our daughters coming back.”

Steve Walker

House 44

When Monocle visits documentary filmmaker Walker together with his wife and two daughters, they’re midway between moving from a house that he rented (51) to one they have bought (44). Compared to many at Halen they are relative newcomers, having only lived here a couple of years. “As soon as we had our first child we wanted to move away from the city [Bern],” he says.

“I grew up in a small mountain village and this is what it felt like.” There aren’t many estates like Halen in the mountain villages of Switzerland but it was the freedom of the children that swung it for the Walkers. “You open the door and they go out and play – there’s always things for them to do and people for them to be with and you feel safe. I’m not here for the architecture, which many people say is their first love – for us it’s because it’s the best place we can imagine to bring up children.”

Fritz Thormann

House 53

Thormann, an architect and urban planner now in his eighties, worked with Atelier 5 on constructing Halen and has lived in the same house since it was completed. “My wife and I have had five children here and now it’s just us,” he says, “but we’re proof that the flexible layout works.” He points out the idiocy that Halen is now protected and permission has to be granted to make any structural changes. “It’s nonsense and against our founding principle that owners would need to adapt the houses to suit their needs.” Seated on his original Mies van der Rohe dining chairs he reveals the secret to Halen’s success. “Life in a well-equipped community is cheaper. You might have small rooms in your home but most of your time, particularly for children, is spent together in communal areas. There’s just no room for everyone to have everything in their own home – it’s not economical.”

Bernhard Egger and Christof Huber

House 75

Architect Egger lives with his partner Huber in the house that was the original show home when Atelier 5 was trying to sell the houses at Halen. It is the only house with an entire wall of glass in the room on the top floor (now Egger’s office) with a breathtaking view down the valley and across to the mountains. They describe living in Halen in a rather animal capacity: “The balance of social and private lives works perfectly,” Huber explains.

“In summer people take food outside and eat together. It’s the most communicative environment I’ve lived in and I used to live in city centres.” But come winter the doors close and people recede inside as if for hibernation. One gets the sense this might be a relief after the hectic social whirl of warmer days. “Come spring though, people emerge and it’s always lovely to see everyone again,” Egger says.

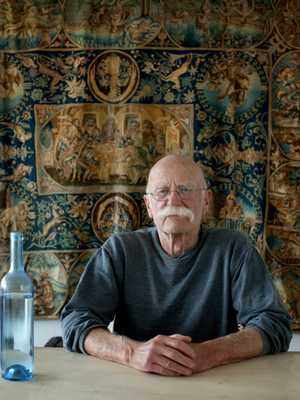

Urs Heinberg

House 15

Heinberg, a professor of urban planning at the Bern University of Applied Sciences, has lived in Halen with his wife for nine years. With his USM cabinets (a prerequisite in most Swiss homes) stuffed full of books about heroes of modernism – Paul Klee, Eileen Gray, Le Corbusier – Heinberg has an academic take on Halen’s success. “It has achieved what so few other estates managed: to provide quality of life for so many people while taking up so little space on the ground.

It affords total privacy and social community as you wish,” he says. Halen remains Atelier 5’s biggest success, achieving the balance Heinberg describes and critical acclaim, however limited that may be. Heinberg feels the lack of more widespread Halen replicas is due to the fact it is in Switzerland. “This way of living is very un-Swiss. But you see elements of the design elsewhere, all over the world.”